Pambatti Flashback

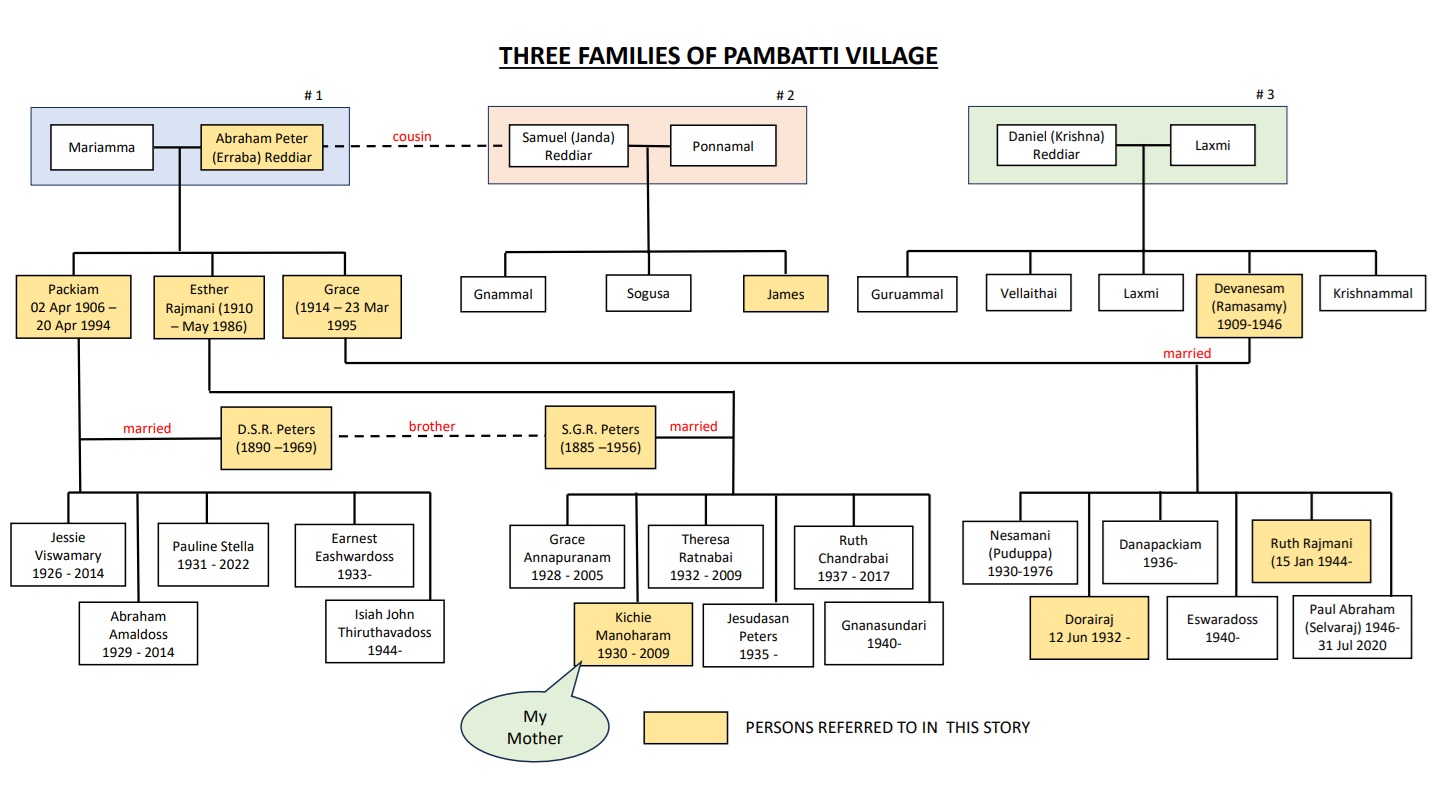

My brother Jerome, who had painstakingly researched to trace our family’s roots revealed that many relatives on my mother’s side, originated from three families of Pambatti village almost two centuries ago (refer to attached family tree). Pambatti is a village in the central part of Tamil Nadu. My maternal great grandfather was Abraham Reddiar, a landlord in this village in Virudhnagar District of Tamil Nadu today. In addition, the families of Samuel (Janda) Reddiar and Daniel (Krishna) Reddiar in Pambatti were among our earliest-known relatives. Abraham was also called Errabba (meaning red in Telegu) on account of his fair and ruddy skin. Errabba married a Christian woman – Mariamma. They had three daughters – Packiam, Esther Rajmani (my maternal grandmother) and Grace. The two elder sisters – Packiam and Esther married two brothers of the Peters family from Madurai. The third daughter, Grace married Devanesam from the Pambatti village itself. Their mother, Mariamma worked as a teacher in a mission school in Pambatti. This mission school celebrated its centenary celebration in 2008. My uncle Dorairaj, who was also born in Pambatti recently shared some photographs of this school. This reminded me of some nostalgic moments I had spent as a ten-year-old at my mother’s ancestral village.

Bus Journey

My earliest recollection of Pambatti was of the 1970s. During our vacations down south, my mother along with my brothers and sisters boarded a bus from Madurai to Kariapatti, a town about 32 kms away. There were regional bus transport services which were named after various royal dynasties that had ruled Tamil Nadu during the medieval period like Chola, Cheran, Pallavan, Pandian and so on. My mother told stories about these kingdoms during our bus travels. Taxis and cars were rarely seen on the road. One aspect of the bus surprised me. Unlike buses in Delhi that had glass windows, I still remember that the buses in Madurai in those days had windows made of a simple rexine sheet that could be rolled up and down as per requirement by the passengers. My mother’s uncle, James Periappa (meaning elder father in Tamil) had come to receive my mother at Kariapatti Bus Stand. Pambatti village was located about 6 kms further away and was not served by any public transport. My mother was expecting a bullock cart which is the usual mode of transport in those days. Apparently, one of the iron pins which holds the wheels to the axle of the cart had fallen off en-route. Since that would take a long time to repair, James uncle walked down leaving the bullock-cart to receive us. The luggage was suitably divided amongst all of us and we all walked in the hot sun to reach the village after about an hour and half later. Along the way, we saw a lake full of beautiful lotus flowers in shades of pink, violet and yellow in full bloom.

Indian G String

When my mother exclaimed about the beauty of these lotus flowers, James uncle directed a small boy wearing just a vest and shorts to get a few lotus flowers from the lake. The little fellow obediently went around a bush and reappeared again without his vest and shorts. He had folded his vest neatly around the cord on his waist from front to back to hide crucial parts of his body and jumped into the water. Before long, he brought some beautiful lotus flowers and also a lotus fruit. My mother was super impressed with the beautiful flowers. Meanwhile, I was still wondering how the boy’s vest got transformed into a G String in a matter of seconds. Incidentally, this G String in Tamil was called a ‘kumono‘. Yes, this sounds like ‘kimono’ – the Japanese traditional national dress but is far from it.

Mini-Andhra in Tamil Nadu

I observed was that my mother and uncle were not speaking in Tamil but Telugu. Telugu language was their mother tongue. In my uncle’s house, everyone spoke in Telugu and we could not understand a word in their conversation. My mother explained how their ancestors had migrated from a village in Guntur in Andhra Pradesh and settled in Pambatti. These families maintained their identity by continuing to speak in Telugu though many Tamil customs were now being followed over a period. I soon realised that my mother could speak in Telugu but not read and write. Notwitstanding this, in Pambatti, I could sense a mini-Andhra in the heart of Tamil Nadu.

Village Post Office

We stayed in James uncle’s house in Pambatti village for about three to four days. During that time, we made friends with other local children and conversed with them in our broken Tamil. Incidentally, James uncle was also the Post Master of the village and a separate part of his house served as the Village Post Office. In the Post office was a large scale and a set of weights to weigh parcels that were booked there. James uncle showed us how parcels were to be packed to withstand the likely damages they would suffer during transit to their final destination. In addition, there was a black ink pad and the post office seal to stamp the postcards and inland letters.

Cotton Currency

In another part of James uncle’s house was a small grocery shop. Cotton which was grown in the fields there was often used as currency by the villagers to purchase various items from the shop. A villager would bring some cotton which was weighed in the shop and equivalent cost items were made available as per requirement. The cotton so collected was stored in an adjacent room. I remember we used to jump on the mound of cotton fully satisfied that our fall would be cushioned by the thick layer of cotton on the floor. Soon we were covered in lint and we looked like ghosts. I now understood why cotton was called a ‘cash crop’. The shop was also stocked with locally manufactured carbonated soft drinks. These drinks were referred to as ‘Colour’. The drink was sealed by a marble in the mouth of bottle. When the marble was pressed, the gas in the bottle was released with a loud ‘pop’ sound. Being guests of James uncle, we were able to get our favourite ‘Colour’ whenever we felt thirsty. Many years later, I found similar soda bottles in Delhi used to make a popular lemon soda drink called ‘banta‘.

Crown of Thorns

On one of the rounds of the village we were led to the edge of the forest by the local boys. This forest floor was covered with branches with sharp thorns. Each thorn was around one inch long. The thorns pierced right through our rubber sandals. We found it difficult to come out of that place. When we reached home we found that the sole of our feet had been pricked multiple times. There was blood oozing out as well. My mother told us about the passion of Christ and the crown of thorns on Jesus’s head and so we had no reason to crib about the thorns that pierced our feet. James uncle put some local lotion to numb the pain and prevent the piercings from getting septic. Luckily for us, wounds on the soles of our feet healed soon.

Scary Scorpion

During the night, we all slept on the roof of James uncle’s house. Sleeping mats were placed on the ground along with a pillow. We could see uncountable stars in the clear sky. A hand fan made from dried Palm Leaf was used to generate a cool breeze if we felt hot. One night, while I was going up the wooden staircase to the roof, I encountered a scorpion. I shouted and used the hand fan to repeatedly hit the scorpion. The scorpion (dead or alive) could not be found later on but in the entire process the hand fan was certainly destroyed. That night, the thought of a scorpion crawling up my leg prevented me from sleeping properly.

Singer’ Sewing Machine

In one corner of the house, my mother spotted an old dusty foot-operated sewing machine lying in a state of disuse. It was an imported ‘Singer’ Sewing machine, a very famous brand then. The machine was not in working condition. The paint had come off. My mother remembered as how she had used this sewing machine to stitch blouses for her sisters and herself. James uncle suggested that my mother take it Delhi and put the machine to some good use. My mother accepted the offer and decided to carry the Singer Sewing machine to Delhi and give it a new lease of life. The machine was dismantled carefully in multiple parts and packed separately for ease of carriage.

My brother and sister complained to my mother for making them carry an old and heavy sewing machine all the way to Delhi which was probably of World War vintage. My mother defended her decision. She said that the Singer machine could do much more that other sewing machines could not do. None of the children and least of all, my father could understand my mother’s logic.

Back in Delhi, my mother took the sewing machine to Singer Showroom in Kamla Nagar. Singer company which had been renamed as Merritt by then, accepted to renovate the machine as a special case. After few months, we received the repainted and shining sewing machine. My mother was pleased with her decision to bring the sewing machine from Pambatti.